?Jasmine Lewis doesn’t want to return to the office because she’s tired of painting a smile on her face.

Lewis is a vice president at a Houston-based home services firm and holds an unofficial role as “Black translator.” The 41-year-old says her colleagues constantly ask her what Black people think about various issues, sometimes even texting her on weekends.

“I am not your performative Black person,” Lewis says. “Translating is exhausting.”

At least when she’s home, she says, there’s no need to mask her irritation since her colleagues can’t see her face.

Avoiding such tokenism and assorted microaggressions from co-workers is just one reason Lewis prefers working from home. Remote work also eliminates a time-sucking commute and would allow her to be physically closer to her soon-to-arrive baby daughter.

“Motherhood changes the way you look at things,” Lewis says.

Many other women and people of color share Lewis’ desire to work from home full time. In fact, workers from those demographics are more likely than white men to say they would rather work remotely, according to new research, primarily because they want to escape the barrage of microaggressions they are often subjected to in the workplace. (Microaggressions are comments or actions that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally express prejudice toward a member of a marginalized group.)

Women add that working from home provides freedom to deal with family responsibilities such as child care.

But granting the wishes of women and people of color may endanger their careers and companies’ attempts to diversify their upper ranks as employers face a new challenge presented by remote and hybrid work arrangements: proximity bias. Many experts worry—and surveys confirm—that managers may forget about people they don’t encounter daily and may grant promotions and high-profile assignments to those in the office. That becomes an even bigger problem if white men make up the bulk of the in-office workforce.

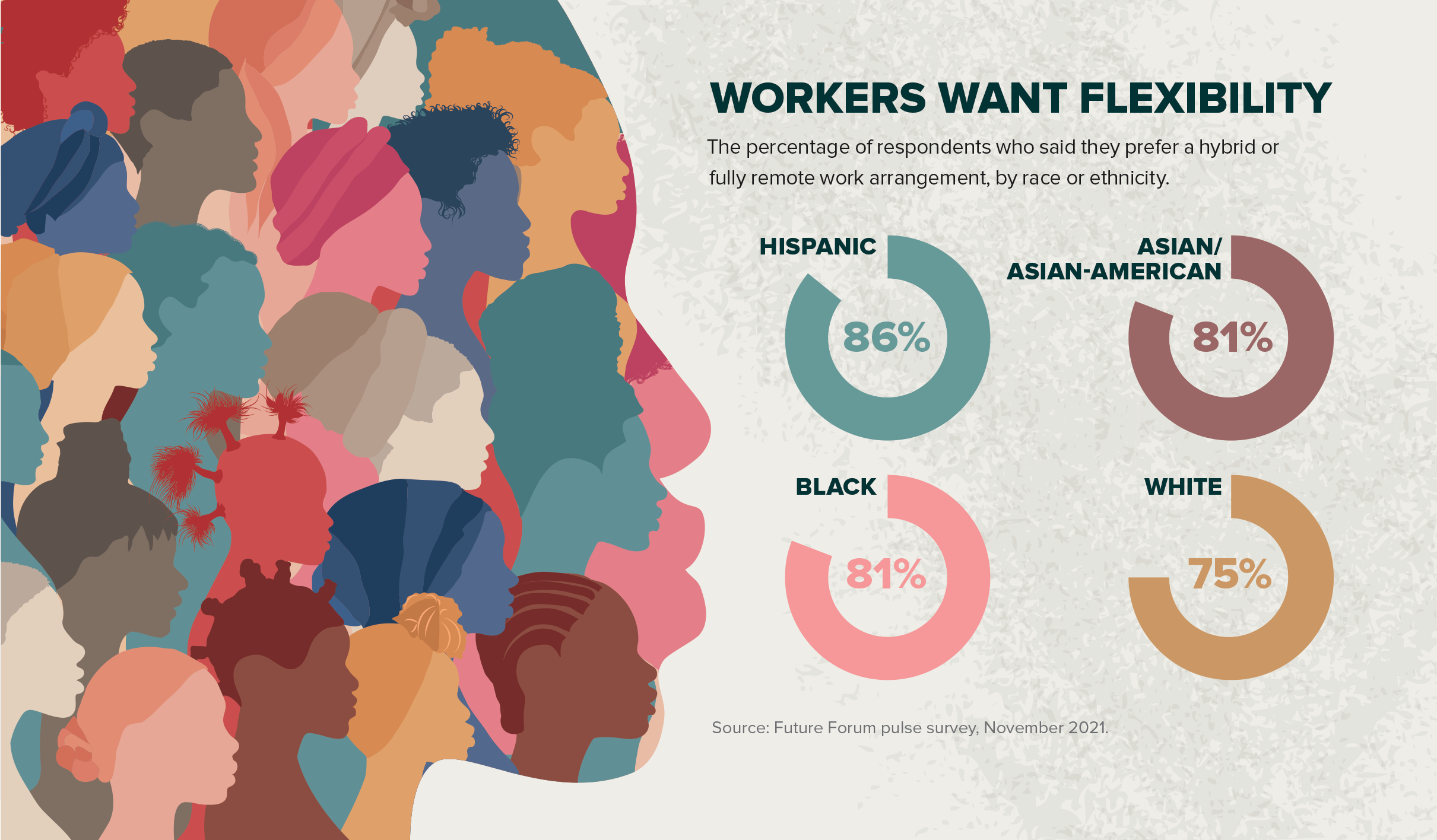

More than 80 percent of Black and Asian or Asian-American knowledge workers in the U.S. say they would prefer hybrid or fully remote work arrangements, as do 86 percent of Hispanic individuals. Three-quarters of white employees feel the same, according to the results of a November 2021 pulse survey of 5,421 U.S. workers from Future Forum, a research consortium set up by Slack. (Unlike those employed at stores, factories or hospitals, knowledge workers tend to have jobs that can be done remotely.) The survey also showed that Black and Hispanic workers’ sense of belonging and fair treatment grew sharply when they worked at home.

Meanwhile, 52 percent of women say they enjoy working remotely and would like to continue to do so, compared with 41 percent of men, according to a recent Harris poll. More than 60 percent of women say they feel more energized working from home, and 58 percent say they are more engaged. Roughly 50 percent of men say they feel more energized and engaged when working from home.

Stubborn Resistance

Managers, however, don’t hold remote work in high regard. Nearly 70 percent of supervisors believe that remote workers are more easily replaceable than onsite workers, according to a study released last July by the Society for Human Resource Management. About 42 percent of supervisors say they sometimes forget about remote workers when assigning tasks, and nearly three-quarters say they would prefer all of their subordinates to be in the office.

“Managers are kind of shrugging their shoulders and saying, ‘Yes, you can be remote, but it will impact your career,’ ” says Mimi Fox Melton, chief executive officer at Code2040, a San Francisco-based nonprofit dedicated to diversifying the tech industry.

“The role of management is to give workers the support and clarity to do their best work,” Melton adds. “It’s not a worker’s job to make sure they are in the line of sight of a manager and wave their hands and say, ‘Look at me.’ ”

Companies hope to avoid proximity bias by training managers to be more inclusive so remote workers’ careers don’t stall. Employers are also upgrading technology for more-seamless remote interactions, while simultaneously encouraging senior executives to demonstrate that remote work is acceptable by engaging in it, too. Others are hiring directors of remote or hybrid work to better accommodate the transition.

This is all happening as more companies consider achievement of diversity goals when making decisions about executive compensation. Salesforce, for example, announced in February that it was linking executive pay to diversity goals.

The last thing companies need is more obstacles to achieving diversity, experts agree. White men hold about 62 percent of C-suite positions, compared with white women at 20 percent, according to a 2021 survey by LeanIn.org and McKinsey & Co. The disparity is more acute with people of color: Men of color hold 13 percent of C-suite roles, while women of color hold only 4 percent.

Uncertainty Reigns

As companies struggle to improve their diversity, equity and inclusion (DE&I) programs, they’re also scrambling to create plans for hybrid work.

“No one’s figured this all out yet,” says Elena Richards, chief diversity and inclusion officer at KPMG. “Communication will be key.”

Of course, it’s possible that DE&I programs will get a boost from remote work. Job candidates are no longer limited by geography, and a broader range of mentors and sponsors may be available if meetings don’t need to be office-based. Remote work also levels the playing field for those who dislike office schmoozing and socializing.

Remote or hybrid work makes employers look at employees’ work product rather than their bubbly presence at the watercooler, says Pam Cohen, chief research and analytics officer of WerkLabs, the research division of The Mom Project, a Chicago-based company that provides job-placement services and other support for mothers in the workplace.

However, Cohen notes that employers still must make deliberate efforts to include remote workers in planning and decisions.

“Executives need to realize that remote and flexible working is just the way things are now,” she says, “and they need to communicate an air of respect” for employees who are embracing it.

Fears of enabling a two-tiered employee system pushed some companies, such as San Francisco-based file-hosting service Dropbox, to select a remote-first strategy. “Hybrid approaches may also perpetuate two different employee experiences that could result in barriers to inclusion and inequities with respect to performance or career trajectory,” the company wrote in an October 2020 blog post. “These big-picture problems are nonstarters for us.”

About 40 percent of executives say their top concern about remote work is that inequities will emerge between those working primarily in person and those working primarily remotely, according to the Future Forum survey. Some workers are worried, too: 43 percent believe working onsite will be better for their careers, according to a survey by meQuilibrium and Executive Networks.

There is evidence that remote workers don’t receive the recognition they deserve. A study by Stanford economists concluded that employees who worked remotely reduced their rate of promotion by half, even though they were more productive than those working in the office. The research, which was published in 2015 in The Quarterly Journal of Economics and followed employees who worked at a travel agency in China, has found a new audience amid the move to hybrid work.

Managers Are Key

Leading a team made up of a mix of fully remote and mainly in-office employees is especially challenging for managers because when people are out of sight, they are often also out of mind.

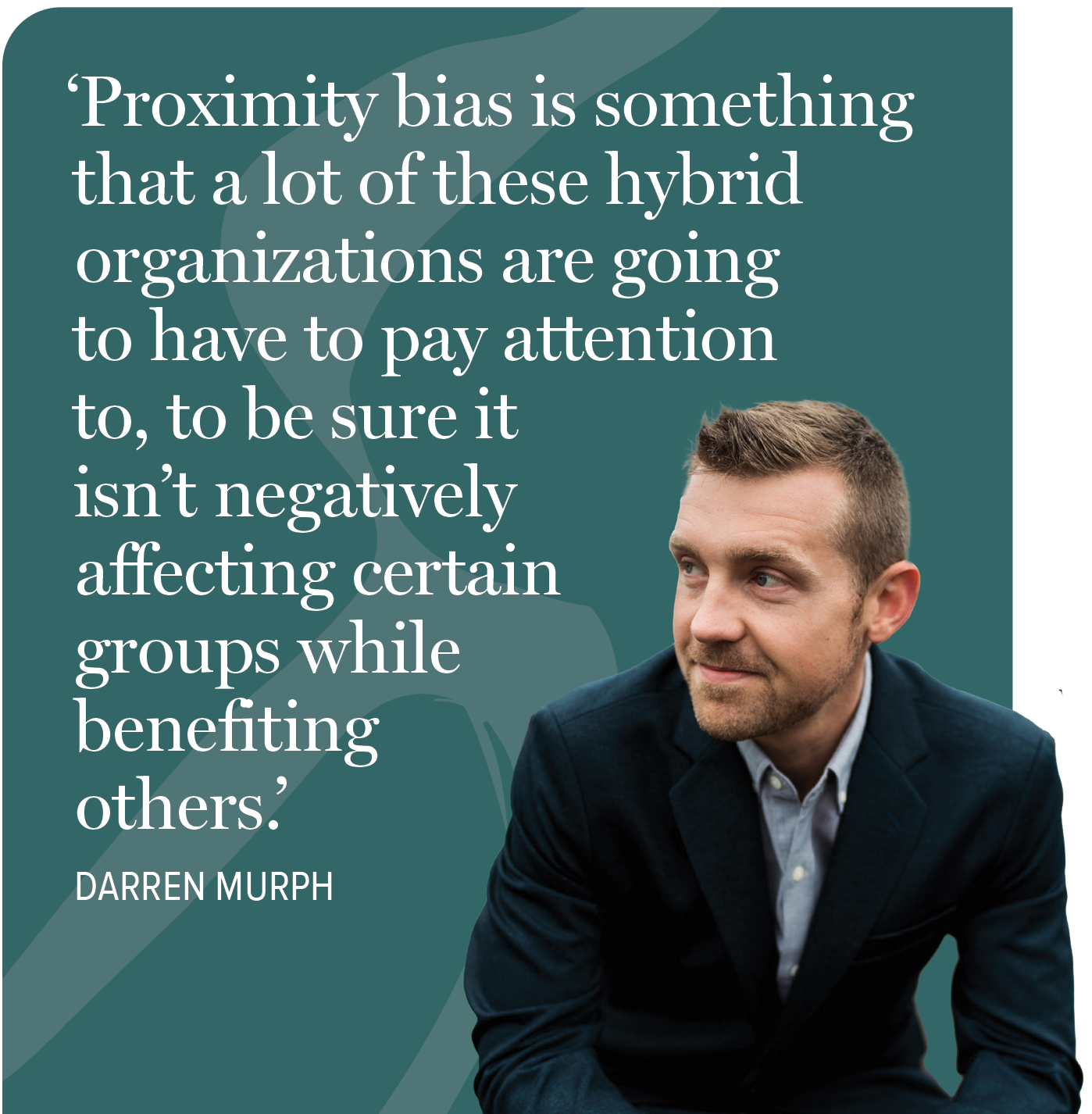

“Proximity bias is something that a lot of these hybrid organizations are going to have to pay attention to, to be sure it isn’t negatively affecting certain groups while benefiting others,” says Darren Murph, head of remote at GitLab Inc., a San Francisco-based software company whose workforce is fully remote. “Without intentionality, hybrid work can be the worst of both worlds.”

It’s rare for companies to designate one person to ensure that remote work works. A study conducted last year by Gartner found that only 14 percent of companies either had or were planning to add in the next two years a “head of hybrid work effectiveness.” However, 57 percent of companies said they either had or would add a head of integrated talent management. That role could certainly include oversight responsibilities related to hybrid and remote work, says Caroline Walsh, a vice president in Gartner’s HR practice. Walsh also predicts that corporate DE&I departments will eventually oversee remote-work issues.

Regardless of what the position is called, Walsh says “organizations must enforce flexibility evenly. The principle must be entrenched in the culture.”

HubSpot, a Cambridge, Mass.-based software maker, has created a workshop for its managers to teach them how to create a cohesive, equitable team in the hybrid environment.

“Enabling managers is absolutely key,” says Celeste Narganes, director of diversity, inclusion and belonging at HubSpot.

In the workshop, managers learn that if some employees plan to attend a meeting virtually, everyone should attend virtually to create inclusivity. Managers are also instructed to make sure everyone has a chance to contribute. They’re further asked to initiate regular check-ins with individuals on the team and to remember that everyone has different life experiences.

“Intentionality is the theme,” Narganes says.

The word “intentionality” is often used by executives to describe how they’ll ensure diversity goals aren’t lost in a hybrid environment, begging the question whether companies were previously intentional in executing DE&I programs.

“Most people don’t check in to ask people how they’re feeling,” Narganes says. “You have quotas to hit. You have numbers to hit. You’re driving toward progress. In most cases, that’s what folks are focused on.”

She isn’t worried about the hybrid environment undermining diversity goals. In fact, she notes, the availability of hybrid work has benefited Black and Indigenous individuals, as well as other people of color: Workforce participation for people in these demographics increased to 34.7 percent last year from 27.4 percent in 2020.

HubSpot also has been able to expand its candidate pool through relationships with Path Forward and DreamCorps, two nonprofits working to diversify the tech industry. Narganes adds that the company has also strengthened its international leadership development programs and allyship efforts.

Shirley Knowles’ mind was racing as a male colleague started petting her braid and asking her questions about her hair, such as the cost and time spent on styling.

Shirley Knowles’ mind was racing as a male colleague started petting her braid and asking her questions about her hair, such as the cost and time spent on styling.

“You’re thinking, ‘Who is this? Why are they touching me? What gives them the right?’ ” Knowles says.

At the same time, she was contemplating how to respond. She knew that if she objected too strongly, she might be labeled “the angry Black woman.”

“You’re doing all this math in your mind when you’re a person of color,” says Knowles, recalling the incident that occurred at a previous employer. “I just gave a short answer and walked away.”

Knowles currently is chief diversity and inclusion officer at Progress Software, based in Burlington, Mass.

Many Black women can relate to similar incidents in which co-workers asked overly personal questions, made inappropriate comments or touched them without permission—and the stress it caused them. The behavior exhibited by Knowles’ male co-worker is an example of a microaggression, which is defined as a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group.

Chester Pierce, a Black psychiatrist and Harvard University professor, coined the term in the 1970s to describe the subtle, everyday discriminatory treatment Black people endure from white people. Over time, microaggressions have a negative, cumulative effect. Many can occur just as easily via Zoom as in person.

Derald Wing Sue, a professor of counseling psychology at Columbia University in New York City, has studied how microaggressions affect other marginalized groups, and now the term has been expanded to include women, other people of color and members of the LGBTQ community.

There are three types of microaggressions:

Microassaults are intentional insults or actions designed to hurt someone, such as using an ethnic slur or walking to the other side of the street to avoid passing certain individuals.

Microinvalidation is an effort to discredit or disparage the experiences of someone who is part of an underrepresented group. An example is telling a woman who describes being harassed that she probably misunderstood what was happening.

Microinsults are comments that disrespect someone’s racial heritage or identity. An example is telling someone that they don’t look Hispanic.

Microaggressions are particularly insidious because people often aren’t deliberately trying to be mean or insulting.

Progress Software’s diversity training includes a session on how to have inclusive conversations. Part of the session includes breaking employees into groups to role-play in different scenarios.

“You have to reach people in a very real way,” Knowles says. —T.A.

New Approaches

Taking a creative approach to scheduling can further help ensure that hybrid work doesn’t undermine diversity goals, says Jessica Jackson, Ph.D., global clinical diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging manager at Modern Health, a San Francisco-based mental health benefits platform for employers. For example, companies can consider having all employees work remotely three days a week and come to the office on the same two days for meetings.

Another option is to rotate those who come into the office so everyone has the opportunity to work in person with the supervisor. However, managers must explain the reason behind the plan so employees understand the purpose.

“As humans, we will participate in what helps us to belong,” Jackson says. “People will want to participate.”

Lewis isn’t concerned that women or people of color will be held back by working remotely, noting that individuals from marginalized groups weren’t getting promoted when they were in the office.

“I could be in somebody’s face all day, and it didn’t matter,” says Lewis, who notes that she’s talking about former workplaces, not her current employer, which she doesn’t want identified. “People will always find you when they want you to do the work.”

Still, some companies are taking extra steps to guard against proximity bias. San Francisco-based Iterable, a consumer marketing company, initiated a “calibration committee,” which consists of six senior executives who ensure that promotion decisions are fair and impartial. Team leaders fill out detailed forms explaining why they believe a certain person merits a promotion. The committee then studies the proposals for signs of bias, comparing promotion rates of remote and hybrid workers to those who work onsite.

“We want to make sure we’re not being unfair to anyone,” says Markita Jack, Iterable’s head of DE&I.

Altria Group Inc. is also looking at promotions through a DE&I lens. Last year, the Richmond, Va.-based tobacco company created an inclusion, diversity and equity ratings system for its people managers, with results based on employee surveys. Starting this year, only those ranked as an “advocate” or “ally” of underrepresented groups are eligible for a promotion.

“The ratings are a way to get at accountability,” says Michael Thorne-Begland, Altria’s vice president and chief inclusion, diversity and equity officer.

The company also plans to track promotions based on where an employee works to ensure that hybrid and remote workers aren’t climbing the ladder at a slower pace than their colleagues.

About one-third of the company’s employees are eligible to work remotely at least part time, Thorne-Begland says, and decisions about what’s possible will be made through discussions with their managers.

“This model is about employee empowerment,” he says. “Managers are expected to support them to the extent that they can.”

Thorne-Begland says an internal survey found that senior executives were most likely to want to work in the office. However, he says, Altria’s CEO has told them that they should work outside the facility at least one day a week.

“We want our actions to be in line with what we said,” he says. “Employees need to see you at home or Starbucks.”

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.