?In 2017, the New York State Education Department permitted schools to implement opioid overdose prevention programs, explained Jeffrey P. Simons, superintendent of schools at the East Greenbush School District. The suburban district, with around 4,000 students and about 800 employees, was an early adopter of one such program.

“Some might suggest that it’s not an appropriate place to have an opioid prevention program. I would argue that it is, because it is our responsibility to take care of people,” Simons said. “My view is you need to take care of your people, and having supports in place serves the broader mission of an organization that wants to have a positive, safe and healthy employment culture.”

An estimated 107,600 people in the U.S. died from opioid overdoses in 2021, the CDC reported. Administering naloxone—a medication that reverses the effects of opioids—to a person who has overdosed can save their life. But it must be administered quickly to avoid potential respiratory problems, said Nash Alexander, chief operating officer of Wilton EMS in Upstate New York. Having naloxone in the workplace means an employer can respond faster than the local EMS, he added, as responders can take between five and 20 minutes to arrive on scene.

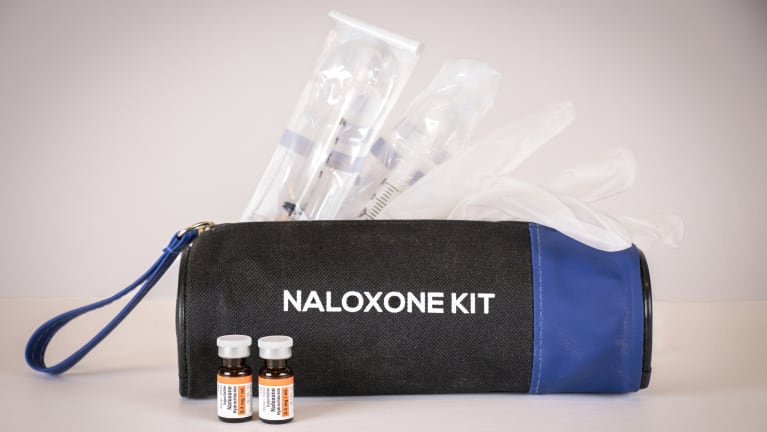

With Narcan (a brand name of naloxone typically administered as nasal spray) now available over the counter, employers that make the medication part of a workplace safety kit can rapidly assist an individual experiencing an overdose. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, workplace overdose-related deaths totaled nearly 400 in 2020, leading experts to urge employers to take an active role in battling the opioid epidemic.

[SHRM members-only HR Q&A: Should employers keep naloxone in the workplace?]

The Case for Naloxone in the Workplace

Adam Calli, SHRM-SCP, principal consultant of Arc Human Capital LLC in Washington, D.C., draws comparisons between the availability of Automated External Defibrillators (AEDs) and naloxone in the workplace.

“Though extreme opioid consumption isn’t typically considered a hazard of the workplace, neither is heart disease and related conditions that might cause heart attacks, but companies buy AEDs anyway,” Calli said. “It’s another way to show employees we care and to look out for their overall wellness.”

Although AEDs cost between $1,200 and $3,000, plus staff training, many companies see them as a lifesaving component of their safety kit. The average price per dose of Narcan is $50 to $75.

“Knowing this, you must ask yourself, do you have a workforce likely to overdose on opioids at work where receiving a quick emergency dose of naloxone would be beneficial?” Calli said. “You can consider the number of visitors to your workplaces, such as vendors, clients, etc., as you consider the numbers and likelihood of the overdose.”

After looking at the probability of use, Calli suggests considering:

- What’s the shelf life of the drug? (It’s about 18-24 months.)

- What’s the cost of the drug?

- If you have to dispose of it, how frequently are you likely to do so?

- What’s the expense of those disposals?

- Who will be responsible for monitoring the drug and ordering replacements as needed?

- How easy is it to get the drug to keep a supply on hand?

Opioid overdoses can happen to anyone.

“What if someone starts a new medication? When people have been prescribed opiates, some can have an unexpected reaction,” Alexander said. “Somebody may have had knee surgery and are still on medication when they return to work or may just start a medication and can experience an unintentional reaction. Having naloxone available is for the safety, health and well-being of your team.”

Naloxone Training and Reporting

Of employers interested in making naloxone part of their workplace safety kit, many report not knowing how to respond to an overdose. State and local health departments offer a starting place. For example, when employers work with their local health department in New York State, training and kits are free, according to Alexander. The health department will also help organizations with the required reporting after administering naloxone.

State or industry-specific regulations also provide guidance. For example, Simons explained, New York school districts must employ a medical director—in his district, this individual is a private pediatrician. But currently, only the school’s nurses have received training to administer naloxone; however, district leaders are considering whether to open training up to coaches and extracurricular advisors in accordance with state law.

Training on the use of either the nasal spray or injectable form of naloxone could be included as part of the onboarding process, Calli suggested, as well as in an annual refresher safety training program.

Katie Navarra is a freelance writer based in New York State.