?Editor’s Note: SHRM has partnered with Harvard Business Review to bring you relevant articles on key HR topics and strategies.

Every employee, every workday, makes a decision: Are they only willing to do the minimum work necessary to keep their job? Or are they willing to put more of their energy and effort into their work?

In the last few weeks, many of those who choose the former have self-identified as “quiet quitters.” They reject the idea that work should be a central focus of their life. They resist the expectation of giving their all or putting in extra hours. They say “no” to requests to go beyond what they think should be expected of a person in their position.

In reality, quiet quitting is a new name for an old behavior. Our researchers have been conducting 360-degree leadership assessments for decades, and we’ve regularly asked people to rate whether their “work environment is a place where people want to go the extra mile.” To better understand the current phenomenon of quiet quitting, we looked at our data to try to answer this question: What makes the difference for those who view work as a day prison and others who feel that it gives them meaning and purpose?

Our data indicates that quiet quitting is usually less about an employee’s willingness to work harder and more creatively, and more about a manager’s ability to build a relationship with their employees where they are not counting the minutes until quitting time.

What the Data Shows

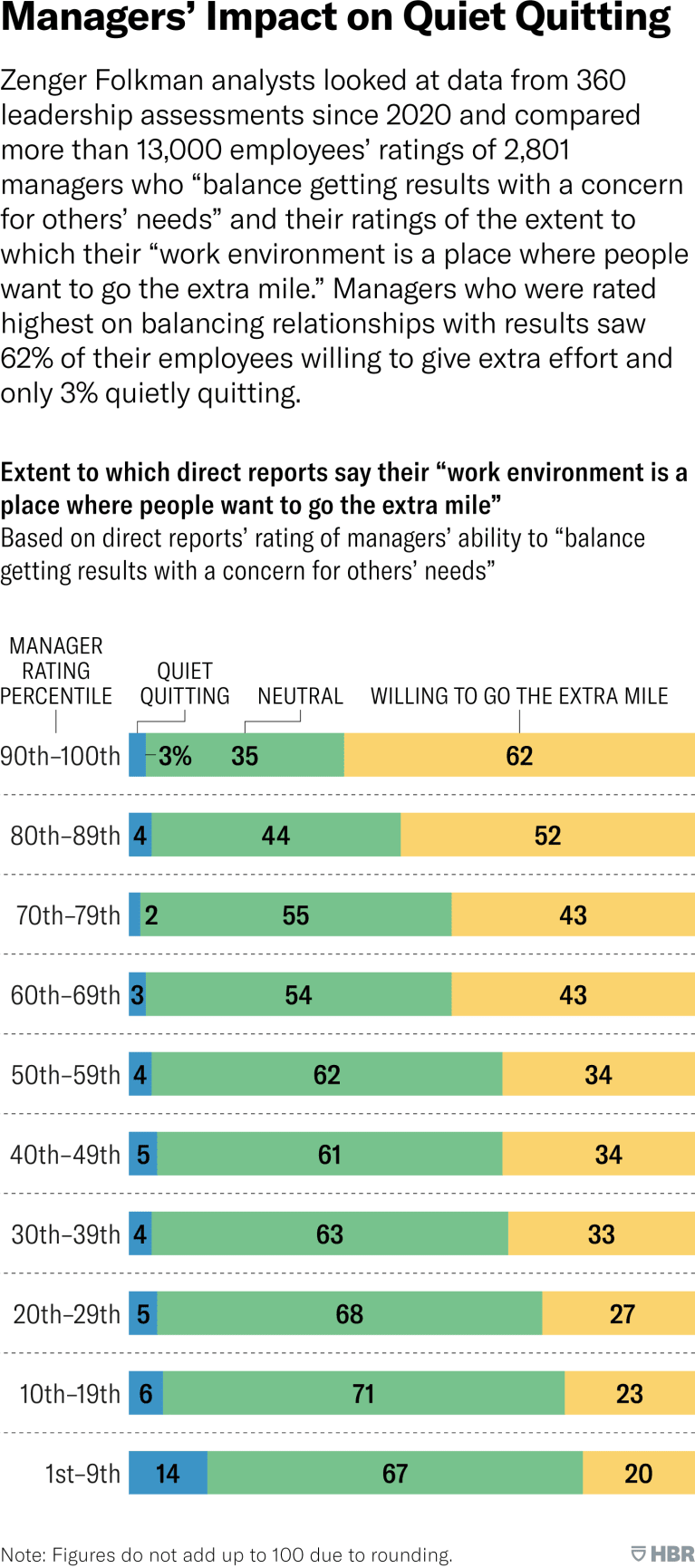

We looked at data gathered since 2020 on 2,801 managers, who were rated by 13,048 direct reports. On average, each manager was rated by five direct reports, and we compared two data points:

- Employees’ ratings of their manager’s ability to “Balance getting results with a concern for others’ needs”

- Employees’ ratings of the extent to which their “work environment is a place where people want to go the extra mile”

The research term we give for those willing to give extra effort is “discretionary effort.” Its effect on organizations can be profound: If you have 10 direct reports and they each give 10% additional effort, the net results of that additional effort are increased productivity.

The graph below shows the results. We found that the least effective managers have three to four times as many people who fall in the “quiet quitting” category compared to the most effective leaders. These managers had 14% of their direct reports quietly quitting, and only 20% were willing to give extra effort. But those who were rated the highest at balancing results with relationships saw 62% of their direct reports willing to give extra effort, while only 3% were quietly quitting.

Many people, at some point in their career, have worked for a manager that moved them toward quiet quitting. This comes from feeling undervalued and unappreciated. It’s possible that the managers were biased or they engaged in behavior that was inappropriate. Employees’ lack of motivation was a reaction to the actions of the manager.

Many people, at some point in their career, have worked for a manager that moved them toward quiet quitting. This comes from feeling undervalued and unappreciated. It’s possible that the managers were biased or they engaged in behavior that was inappropriate. Employees’ lack of motivation was a reaction to the actions of the manager.

Most mid-career employees have also worked for a leader for whom they had a strong desire to do everything possible to accomplish goals and objectives. Occasionally working late or starting early was not resented because this manager inspired them.

What to Do If You Manage a ‘Quiet Quitter’

Suppose you have multiple employees who you believe to be quietly quitting. In that case, an excellent question to ask yourself is: Is this a problem with my direct reports, or is this a problem with me and my leadership abilities?

If you’re confident in your leadership abilities and only one of your direct reports is unmotivated, that may not be your fault. As the above chart shows, 3% or 4% of the best managers had direct reports who were quietly quitting.

Either way, take a hard look at your approach toward getting results with your team members. When asking your direct reports for increased productivity, do you go out of your way to make sure that team members feel valued? Open and honest dialogue with colleagues about the expectations each party has of the other goes a long way.

The most important factor is trust. When we analyzed data from more than 113,000 leaders to find the top behavior that helps effective leaders balance results with their concern for team members, the number one behavior that helped was trust. When direct reports trusted their leader, they also assumed that the manager cared about them and was concerned about their wellbeing.

Our research has linked trust to three behaviors. First, having positive relationships with all of your direct reports. This means you look forward to connecting and enjoy talking to them. Common interests bind you together, while differences are stimulating. Some team members make it easy to have a positive relationship. Others are more challenging. This is often a result of differences (age, gender, ethnicity or political orientation). Look for and discover common ground with these team members to build mutual trust.

The second element of trust is consistency. In addition to being totally honest, leaders need to deliver on what they promise. Most leaders believe they are more consistent than others perceive them.

The third element that builds trust is expertise. Do you know your job well? Are you out of date on any aspects of your work? Do others trust your opinions and your advice? Experts can bring clarity, a path forward and clear insight to build trust.

By building a trusting relationship with all of your direct reports, the possibility of them quietly quitting dissipates significantly. The approach leaders took to drive for results from employees in the past is not the same approach we use today. We are building safer, more inclusive and positive workplaces, and we must continue to do better.

It’s easy to place the blame for quiet quitting on lazy or unmotivated workers, but instead, this research is telling us to look within and recognize that individuals want to give their energy, creativity, time and enthusiasm to the organizations and leaders that deserve it.

Jack Zenger is the CEO of Zenger/Folkman, a leadership development consultancy. He is a coauthor with Joseph Folkman of the book Speed: How Leaders Accelerate Successful Execution (McGraw Hill, 2016). Connect with Jack at twitter.com/jhzenger.Joseph Folkman is the president of Zenger/Folkman, a leadership development consultancy. Connect with Joe at twitter.com/joefolkman.

This article is reprinted from Harvard Business Review with permission. ©2022. All rights reserved.