?After discovering a co-worker washing out his colostomy bag in the restroom at work, an employee was so disgusted he complained to his boss about it. The manager, similarly disturbed by the behavior, went to HR seeking to fire the co-worker for safety and hygiene violations. But that would have been inappropriate because there were no job-related performance issues at play, recalls Margaret Driscoll, a senior regional HR director at the New England-area company at the time.

So, instead of preparing termination paperwork, Driscoll sat down with the employee to talk. During the conversation, she learned the reason for his behavior: He was washing and reusing his colostomy bag to save money to pay for his wife’s expensive medical treatments.

Driscoll addressed the situation by arranging for benefits to assist with the medical care for the employee’s wife.

“He needed help, and we got him help,” Driscoll says. “We were able to use our current medical plan, plus other resources from the American Cancer Society, to best assist him and his family during those hard times.”

While employee conflicts are inevitable, this incident underscores the importance of talking to employees before irritations and minor disagreements escalate into full-scale warfare.

“You try to understand what the issue is,” says Driscoll, now chief people and culture officer at Blackbaud, a cloud computing provider based in Charleston, S.C. “You have to learn empathy and care.”

Simmering Tensions

Employee conflicts can be a huge distraction at work, leading to reduced productivity and lower morale.

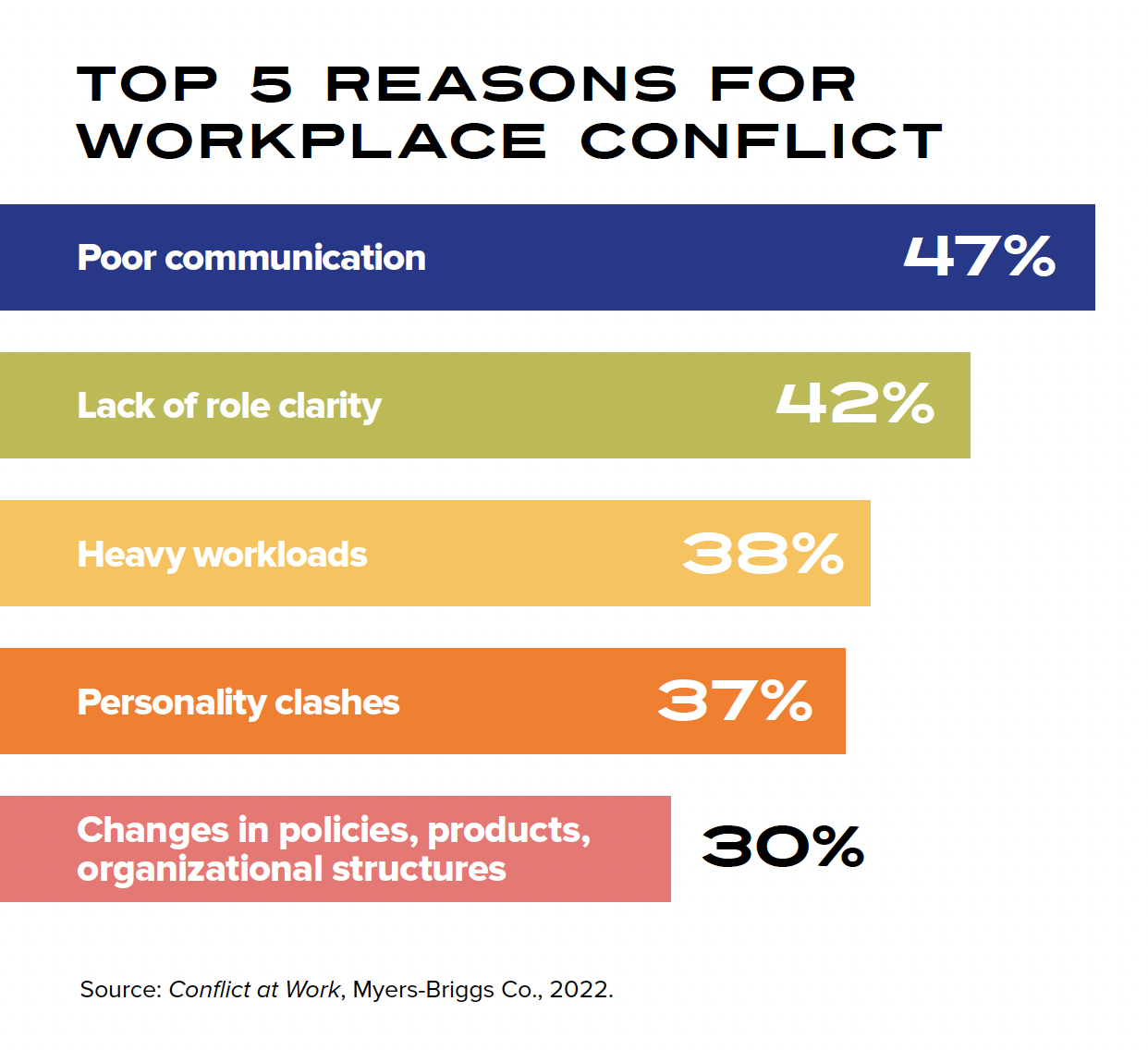

They can also be time-consuming. In fact, employees and managers spend an average of 4.3 hours a week dealing with conflict, according to Conflict at Work, a 2022 global research report by the Myers-Briggs Co. Of the 271 employees surveyed, most of whom were from the U.S. and the United Kingdom, 36 percent said they deal with workplace conflict “often” to “all the time.”

The three most common causes of conflict are poor communication, lack of role clarity and heavy workloads, the survey results showed.

Those conflicts take a toll on job satisfaction. Employees who spend more hours dealing with conflicts are also more likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs than those who spend less time handling conflict, the report concluded.

Of course, not all conflict is unhealthy. Some conflict in the workplace can be a good thing, according to Amy Gallo, author of Getting Along: How to Work with Anyone (Even Difficult People) (Harvard Business Review Press, 2022) andHBR Guide to Dealing with Conflict (Harvard Business Review Press, 2017).

“Healthy conflict includes disagreements, debates or discussions that advance a conversation, meeting or project toward a goal,” Gallo says. “It has lots of benefits, including better work outcomes, innovation, improved relationships, and opportunities for those involved to learn and grow.”

However, “conflict turns unhealthy when people begin to disrespect one another, they get stuck in an endless tug of war, or those involved start focusing on the people rather than the problem,” she says.

Frustrations can be magnified in a remote-work environment, where relationships exist primarily on computer screens. In such situations, “conflict has the ability to simmer longer than if it was in person,” Driscoll says.

Reduce the Heat

HR professionals should encourage managers to work out issues among their team members as long as the complaints don’t raise legal concerns, experts say.

No one in HR wants employees coming to them with minor disagreements such as scheduling conflicts or other matters that fall under a supervisor’s purview, says Myrna L. Maysonet, chief diversity officer and partner at law firm Greenspoon Marder LLP, headquartered in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

“The goal should be solving it at the lowest level possible,” Maysonet says. “You want your manager to manage the everyday issues. HR can’t be the arbitrator of things all the time. Nobody can do that.”

That means HR professionals should train managers on how to resolve employee conflicts and on when to elevate issues to HR.

“HR has the responsibility to ensure the managers are equipped and know where to go for the resources” to handle infighting on their teams, she says. If they don’t know what to do, HR professionals should train them to ask for help.

To defuse tensions within teams, managers should encourage individuals to resolve conflicts among themselves and coach them on how to do so, Gallo advises.

“That said, if you played a role in creating the situation that led to the conflict—perhaps by not communicating clearly or not making clear who is working on what—you have a responsibility to provide whatever information would be helpful to resolving the conflict and to bring the parties together to find a resolution,” she says. “The tricky part is that people often end up in a disagreement without knowing exactly what they’re disagreeing about, so part of your job is to help them clarify what the issue is.”

Some managers—and HR professionals, as well—prefer to avoid conflict or don’t want to admit that they can’t handle a problem themselves.

While it’s tempting to think a problem will go away if ignored, that never happens, says Sharon Lovoy, an HR consultant and communications trainer based in the Birmingham, Ala., area.

“If there is water on the plant floor, you wouldn’t want someone not to say something. That’s a safety issue,” she points out.

The same is true for raising people-related concerns. When a manager comes to HR about a conflict between employees, HR professionals must then weigh whether the issue is a matter of people not getting along or if more-egregious behavior is involved.

If the disagreement is minor, Lovoy favors bringing the two parties together to talk. She suggests HR professionals help alleged offenders understand why their behaviors were problematic and facilitate a process in which those involved in the conflict can have a conversation. Sometimes, the offended party just wants an apology and an acknowledgment that the behavior was unacceptable.

Apologies must be authentic—simply saying “I’m sorry if I offended you” won’t fly—and must include a promise to not repeat the behavior at issue.

Conflict can also occur between departments, especially when they have different agendas, objectives and cultures. If the departments can’t resolve their differences on their own, HR can assist them by trying to understand what’s at stake in the dispute.

“What is the nature of the conflict? What is the core issue that the departments can’t agree on? Once you have a sense of what that is, you can encourage the people in those departments to understand how their goals are connected,” Gallo says.

Then, call attention to how the departments rely on each other.

“Focusing them on a shared goal can often help ease some of the tension,” she says. “It can also be helpful to facilitate a conversation with the relevant stakeholders to help them articulate what they would ideally want an outcome to look like. Then, seek to find common ground in what each department wants.”

Put Out the Fire

Sometimes, the resolution fails, and termination of the offending party is necessary. That was the case some years ago when Kimberley Pasquarella, SHRM-SCP, was the HR director at a call center in the Northeast.

A junior employee was struggling at work because her supervisor was giving her unreasonable deadlines, gatekeeping information, micromanaging and verbally abusing her.

She “was nervous all of the time, constantly in fear of being ridiculed,” recalls Pasquarella, who is now vice president of employee experience at LeadingAge, a nonprofit membership organization for providers of aging services, based in Washington, D.C.

The situation went on for several months, but the employee was afraid to confront her boss and felt uncomfortable going to HR. The problem didn’t come to light until a concerned co-worker informed HR.

The two-member HR department launched an investigation. While there was no evidence of discrimination on the basis of a protected class, it became clear that the manager was undermining the junior employee.

“There was definitely a pattern,” Pasquarella says. “It started out by the person sort of micromanaging to the point [where] the employee really couldn’t do her job. Everything she did was not up to the standards of this person.”

Then, complaints about the supervisor started rolling in from other employees. HR noticed absentee rates were up for her team and for cross-functional teams working directly with her.

Pasquarella and the CEO coached the supervisor. They also brought in an external coach and required the supervisor to attend anti-harassment training. While the individual showed some improvement at first, complaints resurfaced within eight months; ultimately, she was dismissed.

“We really valued what that leader was bringing to the organization, but ultimately, the cost was too great to the organization to allow the behavior” to continue, Pasquarella says. “We took all the steps we felt we could take, but at some point, the accused has to be accountable for themselves.”

An Ounce of Prevention

Preventing conflict is easier to do when an organization has a strong workplace culture.

Here are some tips for building trust, encouraging good conflict, and preventing or addressing destructive conflict:

Survey employees. Conduct annual engagement surveys and have conversations with employees in the interim. Ask employees how well they think conflict is being handled. The results will identify departments that have widespread problems so the employer knows where training and intervention are needed.

Celebrate desired behavior. Have managers seek out opportunities to acknowledge and praise employees.

Welcome dissent. Managers should encourage dissent that’s focused on tasks, strategies and mission. Sometimes, a retreat with an outside facilitator is the best way to get beyond surface conversations.

Create diverse teams. Create work teams whose members have diverse expertise, ways of thinking and backgrounds. Appointing a rotating devil’s advocate is a good way to stir up productive conflict.

Create accountability. This can help prevent conflicts, because many fights arise from a lack of clarity over who has the final authority to make a decision. Making sure that roles are well-established and communicated clearly prevents problems from arising.

Encourage people to manage their own conflicts. Tell employees to work out conflict at the level where it happens, instead of pushing it up the organizational chain. Doing so will give people the confidence that they are capable of handling these issues on their own.

Provide training. Employers can help people learn the skills they need to handle conflict by sending them to courses or recommending helpful books. Conflicts tend to become emotionally fraught when someone chooses not to focus on the issue at hand, but rather, to question another person’s competency, autonomy or integrity.

Source: SHRM Toolkit: Managing Workplace Conflict.

Lay the Groundwork

Employers should have certain protocols in place for handling employee conflicts. For example, organizations should craft a written anti-discrimination policy, establish reporting procedures and develop a documentation process for information gathered during an investigation, says Maysonet, the Fort Lauderdale attorney.

Those investigations should involve talking to both parties, as well as witnesses, and gathering evidence. When complaints involve sexual harassment, HR should take immediate steps to separate the parties.

Maysonet’s firm advises HR professionals to be alert for the types of complaints that could turn into big problems, such as discrimination allegations and issues related to the Americans with Disabilities Act or the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Addressing anonymous complaints that don’t contain specifics, such as the date and time of an alleged incident, the department, or the people involved, can be challenging. However, if the department is identified, it’s worth talking to the manager, says David L. Barron, an attorney with Cozen O’Connor who practices in Dallas and Houston. There could be an opportunity for training.

If a worker complains about colleagues’ rude behavior, for example, the manager could take five minutes at the start of a shift to talk to employees about treating each other with respect. Doing so can demonstrate that HR and the manager take complaints seriously.

When dealing with discrimination-related complaints lodged by employees in protected classes, retaliation is an overarching concern, Barron says. Federal law protects individuals against retaliation when they allege discrimination in the workplace, regardless of the validity or reasonableness of the complaint—and retaliation charges are harder for employers to defend against.

It’s important to have a nonretaliation policy and to communicate it to everyone involved in an investigation, including witnesses and supervisors, he says.

A supervisor who has been accused of discriminating against an employee might react by avoiding the employee who complained. However, that can lead to allegations of retaliation, Barron warns. For example, he notes, the employee might say, “ ‘People won’t talk to me anymore. They don’t invite me to lunch anymore. I was not in this meeting. I wasn’t aware of promotional opportunities.’ So it’s a slippery slope.”

Mutual Respect

Ultimately, employee conflicts can be minimized by creating a strong workplace culture built on fairness, trust and mutual respect at all levels of the organization. That requires executives and managers who will lead by example.

To minimize conflicts at Blackbaud, employees are required to complete annual online training on expectations for respectful conduct at work.

“We want our employees to know how their leadership should be communicating to them [and] what to do if you see something,” Driscoll says.

Kathy Gurchiek is an online writer/editor for SHRM who focuses on topics related to students and emerging professionals.

Illustrations by Liana Nagieva/iStock.