?Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.” It’s a line from a U.S. Army ballad famously quoted by Gen. Douglas MacArthur in his farewell address to the U.S. Congress in 1951. MacArthur’s leadership helped the Allies win World War II, and it was the conflict’s veterans who shaped the workplace in the years following SHRM’s founding.

The GIs based their organizations’ structures on their military experience. The result was largely rigid, hierarchical systems that demanded a respect for authority and strictly dictated working styles, hours and promotional structures. The model those old soldiers created has been fading with them—though it hasn’t been completely dismantled—as new generations march into leadership. Few members of the Silent Generation (those born between the mid-1920s and 1945) remain in the workplace, and Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964)—at least the older ones, who also embraced the formula—are increasingly scarce.

That former system worked well for those storied generations, in part because their employment coincided with a long period of economic growth. Their loyalty was rewarded with lifelong employment, steady promotions and pensions. But newer generations have brought different expectations to the workplace, and rigid rules have softened in recent years as a result.

Changes Begin

The tenets of the postwar arrangement began to fray in the 1970s, as globalization devastated many U.S. businesses and the Watergate scandal and the failure of the Vietnam War drove many Baby Boomers to question authority. Younger generations were similarly shaped by the dot-com bust, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Great Recession, the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though every generation endures hardship, Millennials (born 1981 to 1996) and members of Generation Z (born after 1996) have had the distinction of being constantly bombarded with all the details, thanks to 24-hour news access and pervasive social media for some, if not all, of their lives.

As younger generations gain workplace influence, they have made clear that they have no intention of parking in one spot their entire careers. Companies hoping to even be a pitstop must offer flexible and hybrid work schedules, strong mental health benefits, a commitment to diversity and social justice, and good pay.

‘After the stock market crash in 1987, ‘organizations came to expect that people were going to continue putting in those very long hours.’

BEA BOURNE

Generation X (born 1965 to 1980) started to change the status quo by job hopping in numbers that hadn’t been seen previously, says Bruce Tulgan, founder and CEO of RainmakerThinking Inc., a New Haven, Conn.-based management research, training and consulting company. He says members of that generation grew up in the 1970s, when corporate layoffs and divorce became commonplace. Runaway inflation, surging gas prices, the Iran hostage crisis and the threat of nuclear war were hallmarks of the time. Members of Generation X may have been young, but the events cast a pall over society, creating a general sense of malaise.

“There was a feeling that the world didn’t seem safe,” Tulgan says. “Institutions didn’t seem secure and reliable.”

Another reason Generation X switched jobs so frequently was because they had the freedom to do so. There were only 65 million members of that generation, compared with roughly 72 million Baby Boomers.

“There wasn’t enough of us to go around,” says David Stillman, a generational expert and

best-selling author in Minneapolis who wrote Gen Z @ Work: How the Next Generation Is Transforming the Workplace (Harper Business, 2017) with his then-17-year-old son, Jonah.

Baby Boomers Reign

Generation X’s attitudes contrasted sharply with those of Baby Boomers, who set the standard for hamster-wheel-like working schedules. Baby Boomers faced competition from peers, for sure, but they were entering their prime working years in the early 1980s, as the country exited a recession and conspicuous consumption ruled the day. Baby Boomers logged excruciatingly long hours, especially in the financial industry.

For them, the wealthy became cultural icons. For example, Jack Welch, then chairman and chief executive of General Electric, was lionized in the press for his leadership, which was laser-focused on short-term profits and the company’s stock price, with little regard for anything else.

One of the best-known movie lines of the 1980s came from “Wall Street,” when the corporate raider played by Michael Douglas sneered that “Greed is good.”

Until it wasn’t. Ironically, the movie came out two months after the stock market crash in October 1987. The crash was a shock to the national consciousness, and the years that followed brought higher unemployment and a recession just as older members of Generation X were starting their careers. People weren’t working long hours just to accumulate wealth to keep up with the Joneses. They were fighting to keep their jobs.

“Organizations came to expect that people were going to continue putting in those very long hours,” says Bea Bourne, a Texas-based marketing professor and senior lead for diversity, equity and inclusion at Purdue University Global.

Over the years, leaders began realizing they needed to consider the social and emotional needs of their employees, especially as the workplace became more diverse.

“They needed to change assumptions about how employees work to lead high-performance teams,” Bourne explains.

The Millenial Era

Managing with empathy and appreciation became paramount as Millennials entered the workforce. Some were raised by helicopter parents who coddled them and shielded them from disappointment, so employers had to soften long-held norms if they wanted loyal workers.

Millennials are now the largest generation in the workforce and the most diverse segment of the adult population, according to researchers at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

Older generations often malign Millennials for being entitled individuals who need constant praise and don’t want to pay their dues. Yet thanks to Millennials, workplaces offer more benefits that improve employees’ lives, such as family leave, more paid time off and better mental health benefits.

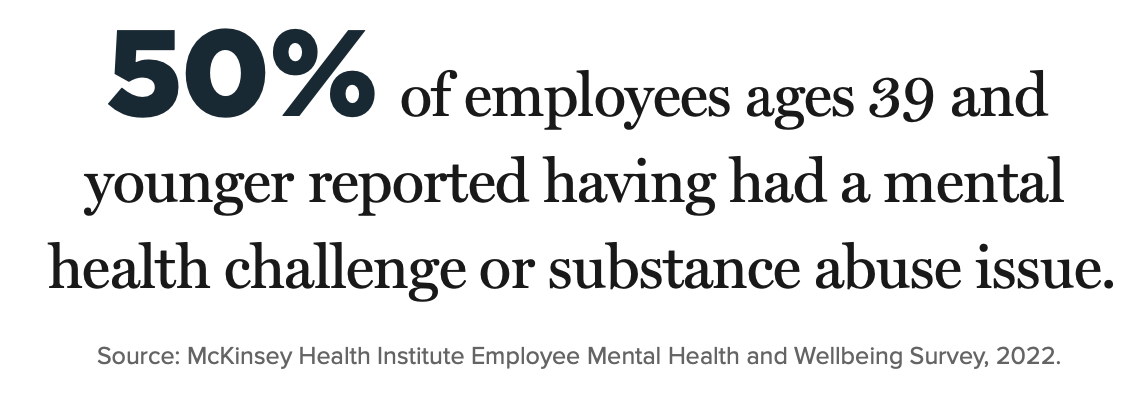

Perhaps given their personal experiences, younger generations have led the charge in starting to normalize discussions about mental health issues at work. They grew up in an era when children and teens were regularly diagnosed and medicated for conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and therefore don’t have the same negative associations with mental illness as their older counterparts.

‘I still think the first thing [company leaders] think about is the return to shareholders.’

CHRISTOPHER J. COLLINS

Plus, many already broadcast the details of their personal lives on social media.

And while the pandemic and George Floyd’s 2020 murder impacted all workplaces and employees, younger workers are more likely to put pressure on employers as a result of these events. For example, they expect their employers to continue offering the flexible work-from-home arrangements introduced during the pandemic, and they want their employers to foster diversity, equity and inclusion in the workplace. Working at an organization that provides meaningful work but allows for time to pursue other passions

and decompress is also important to younger generations.

High Ideals

Many younger people say they are willing to walk out the door if employers don’t match their expectations. Fifty-three percent of Millennials with a hybrid schedule said they would look for another job if their employer ordered them back to the office full time, according to a 2022 study by IWG, a provider of flexible workspaces. Only 33 percent of Baby Boomers felt the same.

Similarly, 46 percent of Millennials and 49 percent of members of Generation Z say they wouldn’t work for an organization that wasn’t proactively taking steps to make its workforce more diverse and its workplace more equitable. Only 33 percent of older workers shared that sentiment, according to a 2022 report from recruitment and staffing company Randstad USA.

Whether younger generations make dramatic headway into turning workplaces into fairer, more socially responsible enterprises remains to be seen. In recent years, the Business Roundtable has called for companies to drop the all-encompassing focus on short-term profits in favor of a long-term approach of investing in their workers and communities. But companies have been slow to adopt a new mindset.

“I still think the first thing [company leaders] think about is the return to shareholders,” says Christopher J. Collins, a professor of human resource studies and director of graduate studies in the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. “I think some of these [social] issues are getting more recognition, but there isn’t a level playing field yet.”

He adds that individuals may start out with lofty notions about having more inclusive leadership and getting more people involved in decision-making. Yet at some point, intentions meet reality and decisions need to be made.

“As every generation ages,” Collins says, “they start to realize the difficulty of managing really big, complex organizations.”

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.

Illustration by Valerie Chiang.