The Creation of the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1970 was a boon to workers, though it took decades of catastrophes to establish the agency.

As factories boomed after the Civil War, workers often had to deal with hazardous chemicals and dangerous machines. State labor bureau reports in the 1870s and 1880s “were full of tragedies that too often struck the unwary or the unlucky,” the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) wrote in a history of job safety laws.

The incidents prompted members of the growing labor movement and social reformers to push for improvements in workplace health and safety, and a hodgepodge of state laws emerged, as some states responded to the demands.

“States with strong safety and health laws tended to lose industry to those with less-stringent ones, which made states competitive and limited their legislative efforts,” the DOL wrote.

In 1907, a mine explosion in Monongah, W.Va., killed 362 coal miners, the worst mine disaster in U.S. history. A few years later, journalist William B. Hard wrote about steel mill safety and estimated that at one Chicago mill, about 1,200 of its 10,000 workers were killed or seriously injured each year.

Such calamities led Congress in 1913 to create the Department of Labor, which was given the goal of improving working conditions. Still, on-the-job injuries and illnesses climbed, with disabling injuries jumping 20 percent during the 1960s and 14,000 people dying on the job each year. At the time, New Jersey Sen. Harrison A. Williams Jr. said, “The knowledge that the industrial accident situation is deteriorating, rather than improving, underscores the need for action now.”

President Lyndon Johnson tried to enact a program to improve workplace safety, but he was unable to overcome opposition. Organized labor supported the measure, while the U.S. Chamber of Commerce opposed it. The bill never came up for a vote by Congress under Johnson.

The move to create OSHA gradually gained traction, however, and in late 1970, President Richard Nixon signed the Williams-Steiger Occupational Safety and Health Act into law. Worker deaths declined, on average, from about 38 per day in 1970 to 13 in 2020, according to OSHA. Additionally, worker injuries and illnesses dropped to 3 per 100 workers in 2020 from 11 in 1972.

“The impact has been huge,” says David Michaels, who was the assistant secretary of labor for OSHA from 2009 to 2017 and is now a professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health at The George Washington University. “The legislation was revolutionary.”

Wins and Challenges

In the first decade after its creation, OSHA issued the first standards for asbestos, lead and carcinogens. It also created protections for whistle-blowers who reported workplace safety concerns.

Since then, OSHA has established standards allowing workers the right to know what chemicals they may have been exposed to, created protections for workers from falls and toxic substances, and offered health and safety training through OSHA education centers.

To be sure, major challenges to ensuring safe workplaces remain. Creating standards at OSHA was always a cumbersome and time-consuming process, and it became even more so when the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act was passed in 1996, according to Richard Fairfax, a consultant with the National Safety Council, an advocacy group based in Itasca, Ill.

The rule was intended to give small businesses a greater voice in establishing safety standards, but it also added more steps to the rulemaking process.

“It’s a lot harder to get standards out,” says Fairfax, a former director of enforcement programs and deputy assistant secretary for OSHA.

Michaels contends that OSHA needs to have more standards. He specifically cites the lack of a standard to govern workplace ergonomics, which can lead to injuries for those performing repetitive work, such as at a poultry processing facility or warehouse.

One notable change that Michaels cites as a positive development is the requirement for many industries to report to OSHA illnesses and injuries that happen in the workplace.

“If things are public, it impacts behavior,” he says.

Another challenge for OSHA is the limited number of inspectors available to monitor workplaces. The agency has roughly 1,850 inspectors to survey 8 million worksites that employ about 130 million workers. That translates to about one compliance officer for every 4,324 worksites.

In fiscal 2021, OSHA conducted 24,333 inspections. Roughly 43 percent of those were programmed inspections, which focus on industries and operations with known potential hazards, such as the use of certain chemicals or combustible dusts. The other inspections were unprogrammed and stemmed from events such as employee complaints or injuries and fatalities.

Over the years, OSHA has created various campaigns, alliances and industry partnerships to help employers create safe workplaces that complement enforcement efforts.

“The size of the agency and the number of inspectors is small,” Fairfax says, “but OSHA has developed successful strategies for improving health and safety. I think they have been successful in getting the word out.”

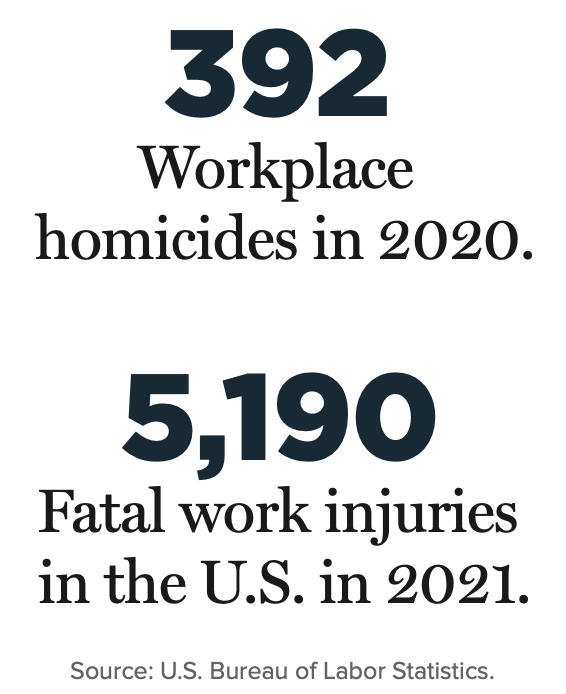

In recent years, HR professionals have been faced with a range of new workplace safety concerns, including gun violence and COVID-19. While worries about the pandemic have waned this year, workplace violence continues to escalate. In fact, in 2020, the most recent year for which figures are available, 392 workplace homicides occurred, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. More than 90 of those involved workers in sales and related activities.

Additionally, more than 37,000 nonfatal, intentional injuries were inflicted on workers, requiring the employee to take at least one day away from work. About half of those incidents involved workers in service industries.

Gun Violence

Workplace gun violence “is a huge issue for employers right now. It seems like it’s an almost daily occurrence,” says Eric Gordon, chair of the labor and employment practice group at Akerman LLP in West Palm Beach, Fla.

In 2022, there were 647 mass shootings, according to the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive. Many of those shootings occurred in the workplace. For example, a gunman killed two employees and three customers at an LGBTQ+ club in Colorado Springs, Colo.; just days later, a manager opened fire in a breakroom at a Walmart in Chesapeake, Va., killing six co-workers.

“Clearly, this is an epidemic,” Gordon says.

Earlier in 2022, following mass shootings at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, which killed 19 students and two teachers, and at a supermarket in a predominantly Black area of Buffalo, N.Y., which killed 10, Congress passed its first gun control legislation in almost 30 years.

“We finally broke the generations-long logjam in Congress to pass lifesaving gun safety legislation,” says Shannon Watts, founder of gun safety organization Moms Demand Action.

Among other things, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act includes incentives for states to establish “red-flag” laws, which allow courts to temporarily seize a gun from a person who is deemed to be a threat to themselves or others, and require deeper background checks for those between the ages of 18 and 21 who want to buy a gun. It also expands a law preventing people convicted of domestic abuse from owning a gun to include romantic partners, rather than just spouses and former spouses.

While the new federal law may help, “this is not going to eliminate workplace violence,” says Gordon, who adds that employers face a “competing interest between the right to bear arms and the need to keep workplaces safe.”

HR professionals can improve safety by creating policies that prohibit guns in the workplace, conducting thorough background checks on applicants and carefully considering whether to hire someone who has a history of violence, according to Gordon.

Susan Ladika is a freelance writer based in Tampa, Fla.

Illustration by Valerie Chiang.