?At a tech conference last fall, Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced his desire to increase the company’s productivity by 20 percent.

Pichai offered an example of how he would accomplish this goal: “Sometimes there are areas to make progress [where] you have three people making decisions. Understanding that and bringing it down to two or one improves your velocity by 20 percent,” Pichai said, according to multiple reports. He acknowledged that Google had become slower as its headcount surged in recent years.

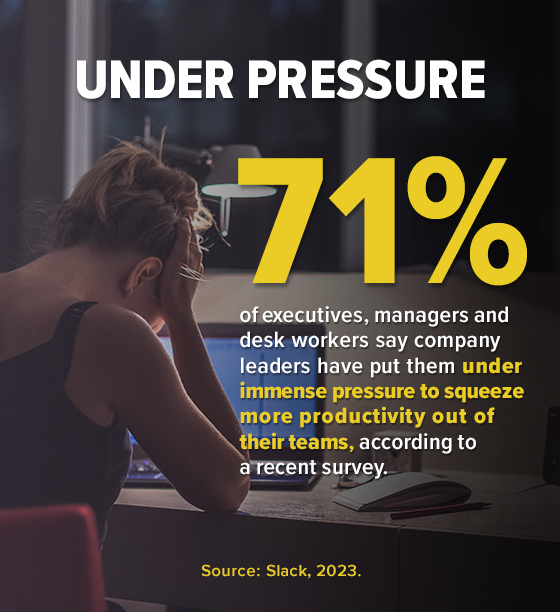

In January, Google announced it was cutting 12,000 jobs, or roughly 6 percent of its staff. Google based the layoffs on employees’ skill sets, performance and productivity, according to media reports. But Pichai is hardly the only CEO worried about productivity. A majority (71 percent) of executives, managers and desk workers say they are under immense pressure from company leadership to squeeze more productivity out of their teams, according to a 2023 survey by Slack, a division of Salesforce.

That’s not surprising. Productivity in the U.S. has fallen in each of the last four quarters, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Beyond that, productivity has been sputtering for the last 15 years, according to consulting firm McKinsey & Company, despite a surge in productivity during the pandemic, when the declines in employment were steeper than the drop in goods produced.

McKinsey found that productivity in the U.S. grew an average of 3 percent from 1995 to 2005, but that growth slowed to just 1.4 percent from 2005 to 2019. While the difference between 3 percent and 1.4 percent may not sound like much, it is significant. For instance, McKinsey says increasing productivity by an average of 2.2 percent annually would add $10 billion to the U.S. economy over a decade and $15,000 to the average worker’s pay.

“There’s a lot of value at stake when it comes to productivity,” says Anu Madgavkar, a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute, the firm’s research arm.

Responding to Declines

Theories abound on why productivity is falling, and, of course, the reasons will differ for individual companies and industries. However, experts agree that certain factors are universal. One is the acute shortage of labor—especially skilled labor. Another is the failure of many companies to significantly invest in digitization and automation. On top of those reasons are employees’ high stress levels and disengagement.

Whether hybrid or remote work is a culprit behind declining productivity remains a matter of debate—though numerous large companies, such as Facebook and JPMorgan Chase, have told employees they must work onsite at least a few days a week. Some company leaders blame excessive meetings and are limiting them so employees can concentrate on their core functions.

The moves leaders make to increase their companies’ productivity will depend on what they believe is holding productivity back, as well as how they measure it. The U.S. Labor Department calculates productivity by comparing the amount of goods and services produced with the amount of effort used to generate them. It’s not the best formula for every business, especially those in which knowledge workers account for most of the staff. Many companies substitute profitability as a measure of productivity, though there are many factors that affect earnings, including inflation and supply chain issues.

Fixing the Culture

Regardless of the definition, experts agree that a productive workforce requires an environment that makes people feel supported and respected while offering opportunities for learning and development.

“The core of what makes a company great in the long term depends quite a bit on the culture,” Madgavkar says. “Fixing the culture is hard to do.”

Employee expectations have changed substantially since the pandemic, with more people wanting to work in organizations that appreciate the need for work/life balance. For many employees, a major component of that has become the ability to work remotely at least some of the time. But several of the first companies to embrace remote work are reversing their decisions as they seek to boost productivity.

Conversely, e-commerce platform Shopify, which is a remote-first company, plans to stay that way. To facilitate work, it eliminated all recurring meetings with more than two participants and declared Wednesdays meeting-free days.

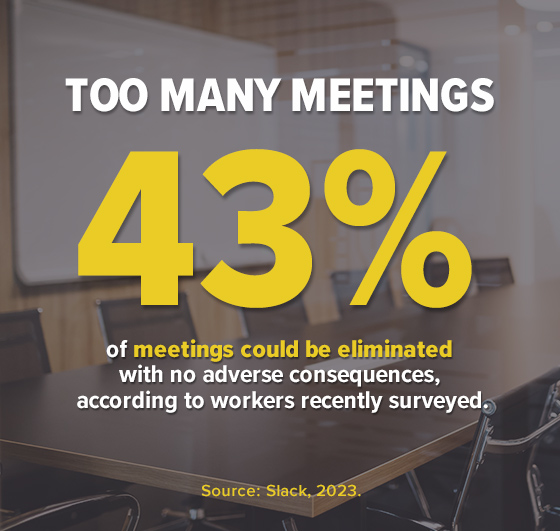

Companies have been suffering from meeting creep. The number of remote meetings employees attended rose 60 percent from 2020 to 2022, according to research by Andrew Brodsky, assistant professor of management at the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin. In the Slack research, those surveyed said nearly 43 percent of their meetings could be eliminated with no adverse consequences.

‘If you’re constantly interrupted with meetings, it makes it very difficult to do the job you were hired for.’

Tia Silas

Tia Silas, Shopify’s chief human resources officer, says the company’s actions eliminated 322,000 hours of meetings, an amount equivalent to 36 years, which has paid off. She says internal data shows some business segments, such as engineering, are on track to complete 25 percent more projects by the end of the year.

“People come to Shopify to build products. This requires focus,” Silas says. “If you’re constantly interrupted with meetings, it makes it very difficult to do the job you were hired for.”

Tracking Takes Off

To ensure employees are indeed performing their jobs, many companies have chosen to monitor them.

A 2022 study by research firm Gartner found that 60 percent of large employers are using tools to track their employees. That figure has doubled since the beginning of the pandemic, when many people were working from home. The study predicts that 70 percent of employers will use employee-tracking tools within the next three years.

Management expert Art Jackson is not a fan of monitoring. “You can’t treat people like they’re not professionals and expect a professional performance,” says Jackson, president and chief consultant at Woodbridge, Va.-based Eagles Nest Performance Management.

Jackson says that if leaders really want to measure their employees’ productivity, they should lay out achievable goals for their reports and regularly confer with them about their progress. “You’re a professional. I expect you to control your own time,” he says.

Another Gartner study done in 2021 found that monitoring may do more harm than good. The report said surveillance can contribute to burnout and remote workers not knowing how to “switch off” during their increasingly longer workdays because of fears of being constantly watched.

However, tracking employee activity has boosted productivity at some companies. Last year, Iron Embers, an Ontario-based manufacturer of fire pits, began requiring employees who construct the products to record how long it took them to complete each stage of the manufacturing process. Co-founder Adrian Tamminga says the move helped the company identify which employees were slower than the rest and perhaps needed more training, as well as how the process could be improved.

Tamminga says there was hardly any pushback from employees. “Our best employees are the ones who embraced the protocol. They want to excel at what they’re doing,” he says. “People were more intentional about what they were doing, knowing that it’s being measured and tracked.”

‘You can’t treat people like they’re not professionals and expect a professional performance.’

Art Jackson

Iron Embers also adjusted its fabrication system based on insights gained from the tracking software. The combination of better-trained workers and a more efficient operating system means the company now needs only 10 employees to accomplish the same goals that formerly required 15. Tamminga says the company didn’t dismiss any workers, though it also didn’t replace employees as they left.

AI investments have also helped Iron Embers’ employees become more effective, Tamminga says. They have been using the generative AI tool ChatGPT to help with marketing, software implementation and web development. That saves roughly $3,500 a month, since the company no longer uses outside vendors.

Tamminga believes these steps have made the company more productive because of lower overhead and more revenue generated per employee.

Investing in Tech

Increased technological investments are critical to increasing productivity, experts say, and U.S. companies appear primed to make them. The number of companies in the U.S. that plan to automate some of their operations is expected to climb to 74 percent in three years, up from 65 percent this year and 51 percent three years ago, according to consulting firm WTW. Additionally, those organizations expect that more than one-quarter (27 percent) of their work will be automated in three years, nearly double the amount three years ago, which should provide productivity dividends.

Nearly 80 percent of respondents in the Slack survey said automating their routine tasks would improve their productivity, though only 45 percent said they have the necessary tools to make their processes easier and more efficient. Nearly 60 percent of those who say they’re more productive now than before the pandemic use automation, compared to 32 percent of their counterparts who don’t.

“Automation is a game changer to get work done more productively,” says Tracey Malcolm, who focuses on the future of work and risk at WTW. She adds that gains will depend on companies’ pace of adopting new technology and having employees who are trained on how to appropriately incorporate it into their functions.

‘Automation is a game changer to get work done more productively.’

Tracey Malcolm

Executives say it’s challenging to measure productivity despite the copious number of tools available to support that effort. “I think just the sheer number of them tells you that it’s a difficult nut to crack,” says Mike McKearin, CEO of Hendersonville, N.C.-based digital marketing agency WE•DO, which specializes in search engine optimization.

McKearin says We-Do’s workers have a defined set of tasks to accomplish as part of their routines, which center on increasing traffic to clients’ websites. However, some tasks are more difficult and time-consuming than others, so he considers that as he examines reports that audit workers’ progress. He also considers whether a worker has boosted visitation to the client’s site, and by how much. However, search engines may change their algorithms, and that can negate workers’ efforts.

When it comes to measuring productivity, there are intangible items to consider as well.

“Are they a team player? Do they have enough grit and hustle? Are they willing to learn?” McKearin asks. “It can never be so black and white. There are so many variables, so you take as many pieces of the puzzle that you do know and take them to heart, and then make a gut call on top of that.”

|

|

The push to improve productivity can go too far, according to state lawmakers, who are passing legislation tied to productivity quotas. The laws are designed to protect warehouse workers who can be injured by scrambling to meet quotas. In May, Minnesota and Washington became the latest states to pass such legislation, while California was the first state to pass such a law. It was approved in 2021 and enacted the following year. Meanwhile, a similar New York law went into effect in June. Bills have been drafted in Illinois and Connecticut, and more may be coming. The laws’ specifications differ, but the basics are similar. They require warehouses to disclose to employees exactly what is expected of them and forbid any quota system from interfering with employees’ breaks. Some laws have provisions that force warehouses to divulge the ramifications for missing quotas. Others compel companies to allow employees access to their productivity data. The laws apply to all companies of a certain size. For example, New York’s law applies to employers with 100 or more workers at a single warehouse, or companies with 1,000 or more employees in warehouses across the state. Despite their differences, the laws stem from the work policies in Amazon’s warehouses. Earlier this year, the nonprofit National Council for Occupational Safety and Health named Amazon as one of its “Dirty Dozen” companies with unsafe practices that put communities and workers at risk. The group reported that four Amazon warehouse workers died on the job last year. It also said the serious injury rate at Amazon warehouses was 6.6 for every 100 workers, more than double the rate of serious injuries at non-Amazon warehouses. The council’s report added that U.S. workers account for 36 percent of Amazon’s warehouse workers worldwide, yet last year, 53 percent of injuries occurred in U.S. warehouses. Also, musculoskeletal problems, including back pain, hernias, carpal tunnel syndrome and tendonitis, are commonly reported among workers at Amazon warehouses. Creating Transparency “What we heard over and over again from workers was that there was this sort of relentless, grueling pace, and it was based on not knowing what was expected and this fear of discipline,” Greenman says. “Opaqueness seemed to be the point.” The new law addresses that problem by creating transparency, Greenman says. “What we heard from workers was that having a standard that you know and understand was really important,” she explains. Greenman adds that workers said the algorithms that determined what was expected were constantly changing, which led workers to further push themselves. “It’s a problem when performance standards are either used or abused in ways that they end up being a worker safety issue,” she says. Amazon spokesperson Rachael Lighty said in May that safety was at the core of everything the company does. “Amazon does not have fixed quotas at our facilities,” she said. “Instead, we assess performance based on safe and achievable expectations and take into account time and tenure, peer performance and adherence to safe work practices. While we know we aren’t perfect, we are committed to continuous improvement when it comes to communicating with and listening to our employees and providing them with the resources they need to be successful.” Amazon says it plans to invest more than $550 million in safety advancements this year after investing $1 billion since 2019. The company further notes it employs 8,000 safety professionals and reduced its injury rate by 11 percent between 2021 and 2022. Greenman says it will likely take two years to determine whether the Minnesota law is having an effect, because it takes time for government agencies to publicly disclose injury reports. It’s also too soon to tell if the law is having an effect in California. “Many employers will likely resist application of the law, so we will see change as workers and the Labor Commissioner’s Office enforce these new rights,” says Tim Shadix, legal director for the Warehouse Worker Resource Center, which helps organize workers in Southern California. “We expect to see measurable improvements in working conditions as more workers learn about their rights and start to hold their employers accountable.” –T.A. |

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.

Explore Further

SHRM provides business leaders with information and resources to respond to sputtering labor productivity.