?The history of labor unions in the United States encompasses more than 150 years of negotiating for better pay, benefits and working conditions for American workers.

The first U.S. labor union was launched in 1866, and in the decades that followed, unions played a critical role in guaranteeing worker safety and fair pay. But after peaking in the mid-1950s, union membership rates have fallen steadily ever since.

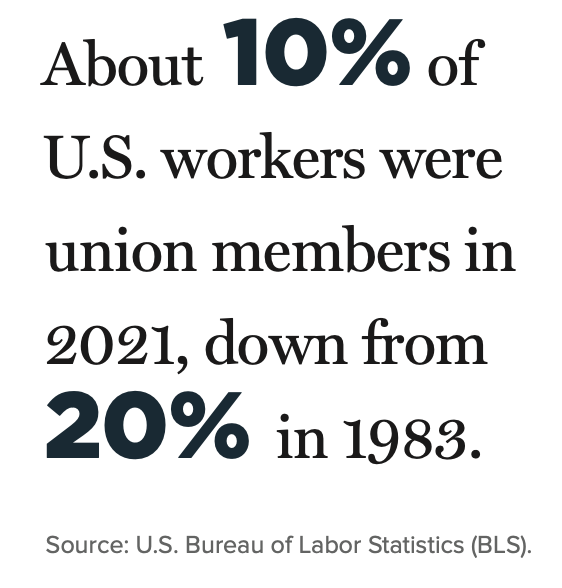

About 10 percent of U.S. workers were union members in 2021, down from 20 percent in 1983, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The union membership rate of public-sector workers (34 percent) was five times higher than the rate of private-sector workers (6 percent) in 2021, and the highest unionization rates were among workers in education, training and library occupations (35 percent) and protective service occupations (33 percent), the BLS reported.

New state and federal laws, and the deindustrialization and globalization of the American economy have all contributed to the decline of union membership, according to Steve Bernstein, an attorney with Fisher Phillips in Tampa, Fla.

In addition, employers have changed their practices in order to recruit and retain good workers; doing so may have reduced the attractiveness of unions. “Frankly, employers are just treating people better” by embracing more fairness and consistency, Bernstein says. “They’ve had little choice. It’s a competitive issue.”

Still, there’s been no lack of attempts to unionize. High-profile wins were notched for new unions at Starbucks and Amazon in recent months, but these victories haven’t been enough to staunch the overall membership decline nationwide.

“Unions are winning a greater percentage of representation elections than they have in quite some time,” Bernstein says. “They’re just not having enough elections.”

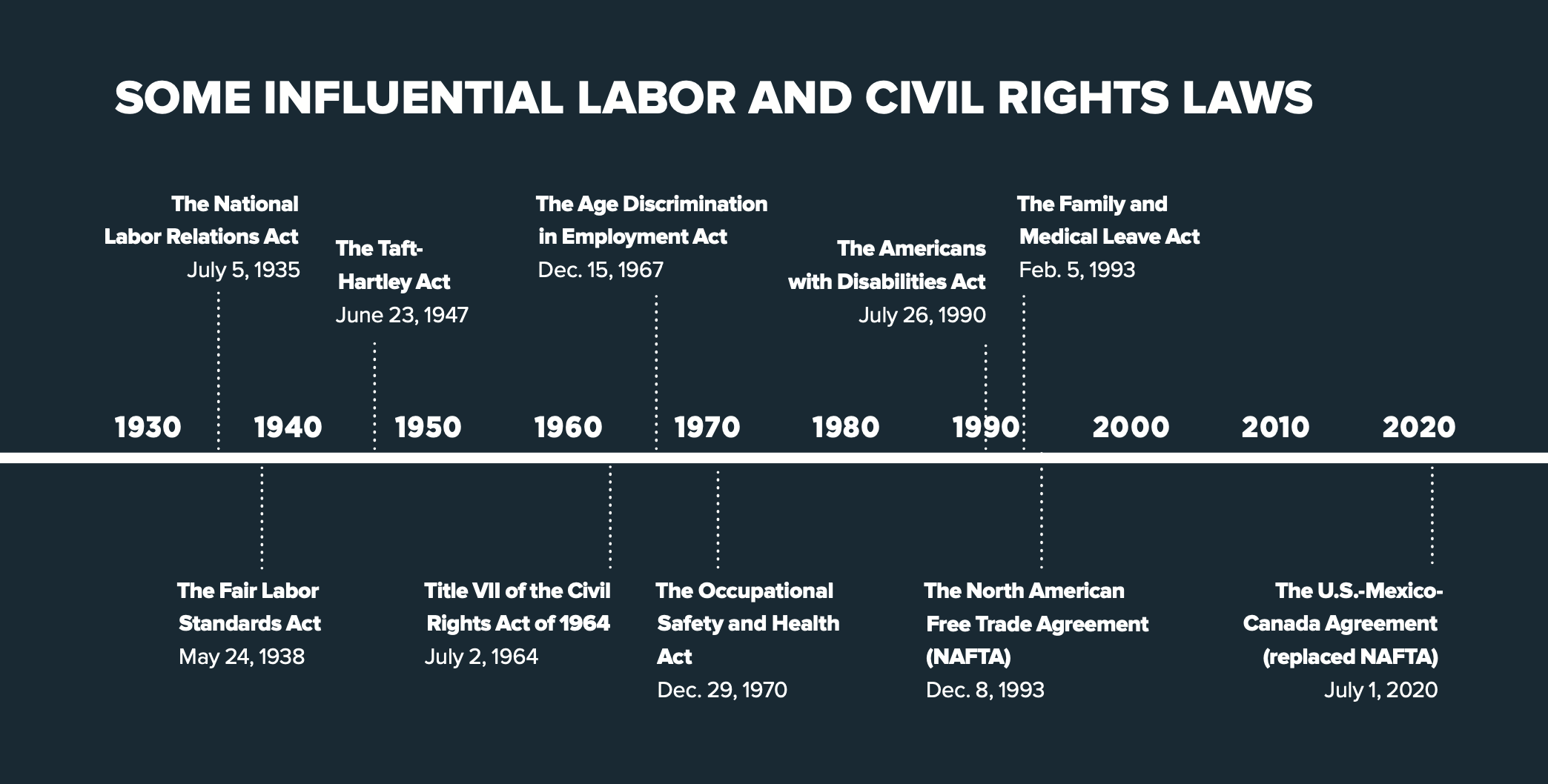

Pivotal Laws

Several federal laws were critical in shaping the power and trajectory of labor unions in this country. They include the National Labor Relations Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act).

In some cases, union representation may have seemed less necessary after state and federal laws were passed to protect workers and improve working conditions.

‘Unions are winning a greater percentage of representation elections than they have in quite some time. They’re just not having enough elections.’

STEVE BERNSTEIN

“A lot of promises that organized labor was making were more impactful in the absence of federal protections,” Bernstein says.

But employers shouldn’t underestimate the influence of unions in getting some of those labor laws passed. Unions pushed harder for the passage of the OSH Act than other institutions, Bernstein notes.

Global Economy

Globalization weakened U.S. labor unions during the last 20 years because many companies moved their operations overseas. This led to the collapse of the U.S. steel industry, which was heavily unionized, according to Matthew Fontana, an attorney with Faegre Drinker in Philadelphia.

“Unions are struggling to find relevance in that dynamic,” Bernstein agrees.

The U.S. economy has become more knowledge-based and service-based. There’s been a shift away from the traditional union industries, such as steel and manufacturing, toward more unions in health care, education, food service and janitorial service.

“Unions had trouble figuring out how to organize the jobs that remained,” Fontana says. “They’ve figured it out now.”

The rise of globalization and the fall of union membership aren’t a blip in the longer trajectory, Bernstein says: “These trends are not short-term trends. They carry the weight of history. It’s going to take a lot to slow down these trends.”

However, public-sector unions didn’t see the same impact from globalization as private-sector unions did. “Public-sector union [membership] has stayed steady,” Fontana says.

‘Because domestic workers work in private residences, they have faced unique challenges in organizing to improve workplace conditions.’

HAEYOUNG YOON

Younger Generation

Today’s entry-level employees want different things than workers in the past did. For example, they are asking for flexible schedules and remote work.

“It’s a fight for the hearts and minds of these workers,” Bernstein says. “They’re more sympathetic. They view unions more favorably. They’re more independent-minded.”

Some young workers gravitate toward unions for social justice and political solidarity.

“That’s something that often surprises employers,” Fontana says. “Workers believe in what unions stand for. They believe collective bargaining can be part of a social justice framework. You’re seeing a real energy among younger folks.”

Unlike in the past, today’s union organizers are a more diverse group and include young workers, women and people of color.

“What you’re seeing now—the changing face of organizing—reflects the changing face of the workforce,” Fontana notes.

An example is the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), which has more than 70 chapters in 30 cities and represents nannies, housecleaners and others who are primarily women of color and immigrants. U.S. domestic workers started unionizing in the 1960s with the National Domestic Workers Union of America before the organization changed its name to NDWA.

“Because domestic workers work in private residences, they have faced unique challenges in organizing to improve workplace conditions,” says Haeyoung Yoon, senior director of policy and advocacy at the NDWA in New York City.

“Domestic workers are specifically excluded from federal labor protections like anti-discrimination and harassment laws and the right to unionize, and almost all domestic workers are not covered under the federal minimum wage law. Despite these barriers, domestic workers have organized for decades.”

While many things have changed about employees and union members, some things have not.

“The worker of today isn’t so different from the worker of yesterday in terms of their core human needs,” Bernstein says. “What people really want in the workplace is to be listened to, to have access to decision-making and to be in a position to at least influence their workplace.”

Leah Shepherd is SHRM’s senior legal editor.

Illustration by Valerie Chiang.